By: Chelsea Parker Follow me on Twitter/X as I continue to still love softball and baseball.

What does softball mean to me? I’ve been asked this question more times than not in my 32 years on this planet. Each time, I can answer it without a single moment of second-guessing. It means everything, and it has since 2001.

Truthfully, before softball, I didn’t have a lot of friends—I have recess friends and the occasional sleepover, but nothing stuck. I played t-ball, a season of three games before I ran off the field, attempted dance lessons, and quit after my mom had spent an ungodly amount of money on tutus and tap shoes due to the fear of my fresh chickenpox scars being mocked by my dance classmates at the age of eight and finally nearly broke my toe attempting to learn soccer in my backyard by fourth grade. I was a timid child with a wild imagination, daydreaming about writing stories about anything and everything. I hung out with my parents instead of most kids my age, watched baseball and NASCAR with my dad, and didn’t know where I belonged in the grand scheme of elementary school, that was until my friend’s mom left a voicemail on my parents answering machine—which I remember word for word. “We’re calling to see if Chelsea would be interested in playing softball. Our first practice is on Saturday!”

I didn’t want to do it. I remember questioning if I would enjoy softball, even though I loved baseball and watched it religiously. I think, looking back, I was terrified as a ten-year-old—not afraid of the ball, but afraid that it would be another moment where I decided I hated it and quit or worse, that I sucked at it. That morning of the first practice, my mom dragged me out of bed with a glove stuck on my right hand, and from there, something lit a spark in me. Despite our team being dreadful that first day, me included, I was stuck in center field with itchy grass, and zero balls were hit to me by my teammates due to horrible offense, and I loved it.

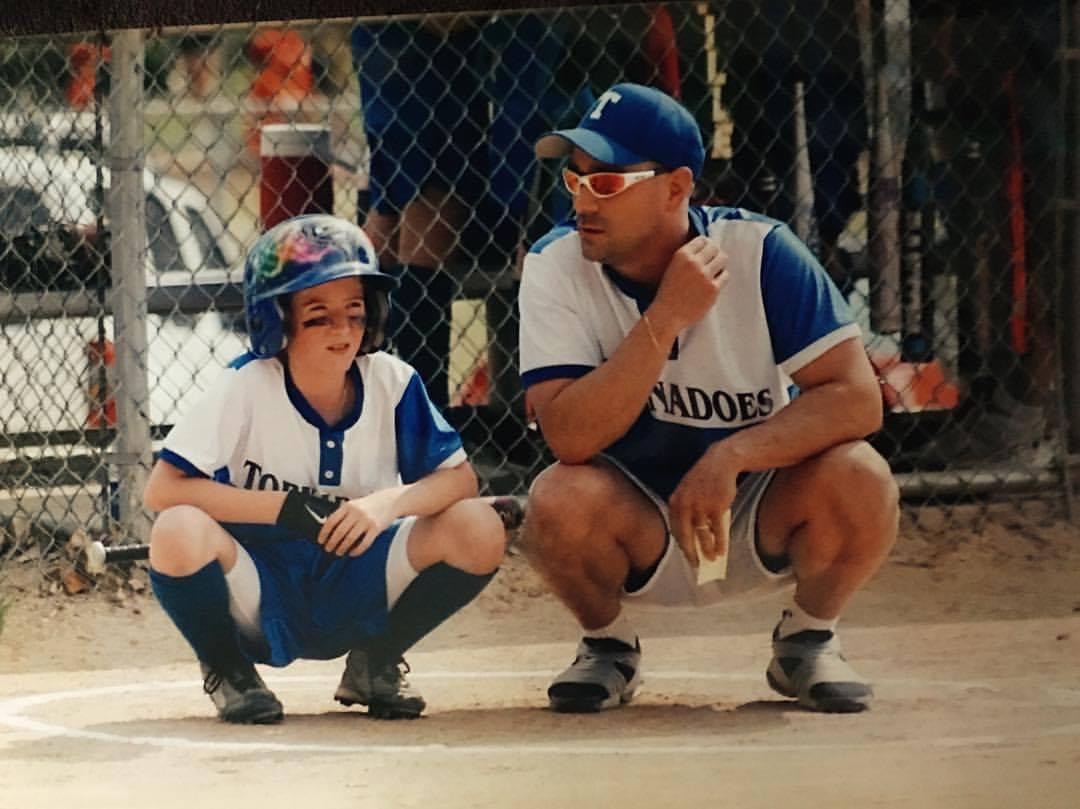

My dad, who beamed with happiness, showed up at the end of practice after work and somehow said the exact word our “coach” wanted to hear. Seconds later, my dad announced to everyone that he would take the head coach role—I laughed. We didn’t win a single game that spring/summer of 2001. Honestly, we didn’t win a game until that fall, and I still don’t know how we did it. We weren’t good. We were the flotsam and jetsam of the ballpark association—the girls who didn’t have a team at first but became a family.

By the end of that first year, I declared that I was tired of the outfield and wanted to be a catcher—mind you, I was a left-handed runt at 10–but that didn’t stop me. I worked hard and proved that I could do it, and I did, at least until middle school when everyone kept growing, and I stayed the same size. My middle school coach, who was not my dad, pulled me from a game during seventh grade and told me I was done catching. I remember leaving the game and sobbing because I didn’t think I could love another position like I did with catching—my shy, awkward personality didn’t matter with the mask on—I was someone else, someone who took charge and wasn’t afraid of anything. However, after meeting my pitching coach, being told repeatedly that I had a natural talent in the pitching circle, and rolling my eyes about 3,000 times, I learned there was a life in softball outside of catching.

The first time I pitched in an actual game, I crapped the bed—embracing my new and unwanted position with my head coach and pitching coach, continuing to annoy a preteen version of myself. They believed in me, but not as much as three other people did—my mom, my dad, and my late grandfather. You see, there were five constants in my life at that time: my parents, my grandpa, softball, and my faith. But as my seventh-grade year rolled on, I lost my grandpa.

On his 70th birthday, February 21, 2004, I made the varsity softball team as a seventh grader. Although this sounds like an outstanding accomplishment, I can honestly say it wasn’t because I was the next Jennie Finch but because they needed me. Our team had never had a winning record—they wouldn’t until I was long gone. But man, my grandpa was so proud. He beamed and told everyone that his Chelsea Brooke had made the varsity team at 12. A week later, he was gone. Much like I would do with baseball 15 years later, in grief, I threw myself into softball. Varsity games, travel ball, multiple pitching coaches, leaving school early on certain days to train out of state with college coaches. Although my dad wasn’t my head coach then, he was still my coach. He and my mom drove me everywhere to ensure I got everything I asked for in softball.

In 2004, after experiencing death for the first time, I played on four softball teams, played 100 games, and dealt with shin splints and one broken nose. Many, me included, didn’t know if I would return after breaking my nose three days after my 13th birthday, but I did. I had already given so much to softball I wasn’t about to give up. I continued to play softball throughout high school, sitting out my sophomore and junior years after my high school had made a coaching change that nobody agreed with when it happened. Then, I transferred to another school, hoping to play for a team considered the best in our hometown. But I returned to my original high school for my senior year and took the field one last season in blue and white.

I quit on my senior night with my entire family in the stands. My career ended in a fiery haze despite everything I had been through—a decision that has remained in my heart for 15 years. Looking back, I think about how much I went through and how much my team went through back then. We didn’t have a field. The school and city argued back and forth while we bounced from recreational field to recreational field—sometimes having to pick up rocks before games off the field to play. When nobody listened, my dad collected the rocks and dumped them on the deck of someone at the Parks and Rec department, begging someone to care about the future of softball in our town. My high school softball program didn’t get a field until I was long gone, but I see it every spring: a new generation of blue and white take the field that I and many others left blood, sweat, and tears on. I write about them each spring for work and remember how much and what softball means to me.